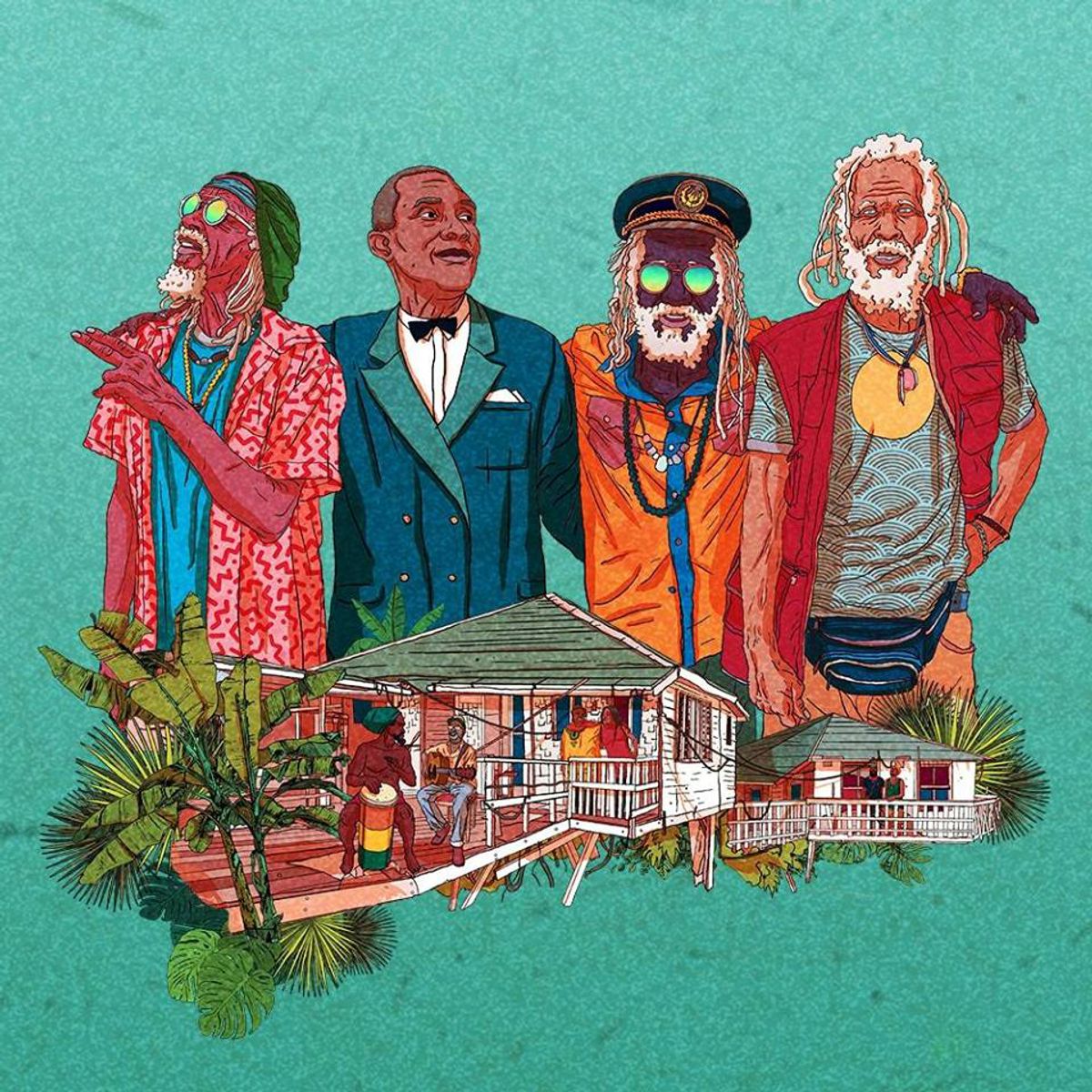

Film4 Summer Screen closes with the UK premiere of Inna de Yard, a love letter to the music of Jamaica starring a superstar group of reggae pioneers. We spoke to the film's British director Peter Webber (Girl With a Pearl Earring, Hannibal Rising) about making this brilliant documentary.

Kingston’s lush scenery and the film's music stays with you for a long time after seeing Inna de Yard. When did you first become fascinated by Jamaica and reggae?

Growing up in West London reggae was in the air, and the occasional song on Top of the Pops. But what really made it click for me, as a teenage punk-rocker, was hearing The Clash’s first album and the amazing cover of the Junior Murvin song ‘Police and Thieves'. That started a love affair with this kind of music that has endured to this day.

I remember the first time going over to Jamaica to meet everyone about six months before filming, I was getting off the plane, getting in a van, not knowing what the schedule was or the full list of who I had been set up to meet. We were driving down the road, and I said, “Where are we going?”, they said, “Oh we’re going to meet a musician, and he’ll cook us some lunch in his backyard”. As we got closer I asked who the musician was and they said, “Cedric”, I went “Cedric? … Cedric Myton… of The Congos?”

One amazing Congos album was one of the mainstays of reggae albums I had listened to as a teenager. So to end up with the singer and songwriter of The Congos, sitting in his backyard, having him cook red snapper and giving out Red Stripes, was really an amazing experience. The whole experience of making this film has been one of the most positive and fascinating of my career.