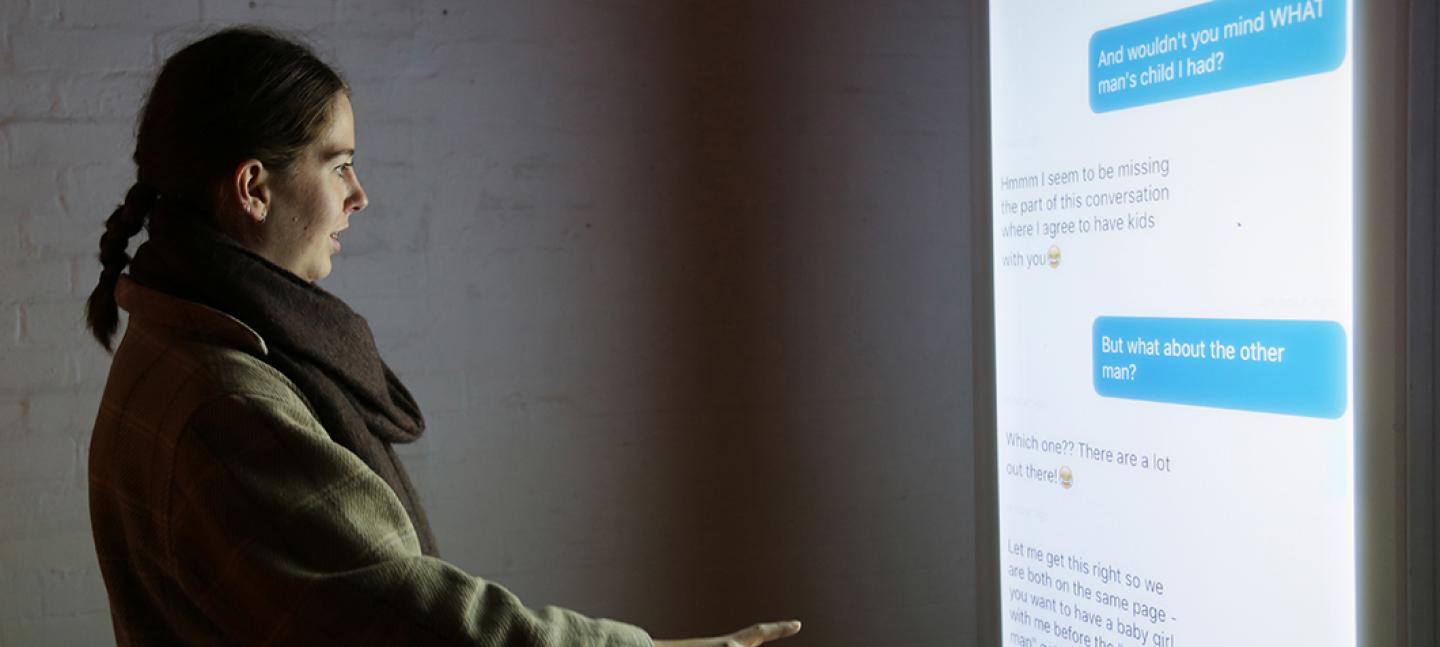

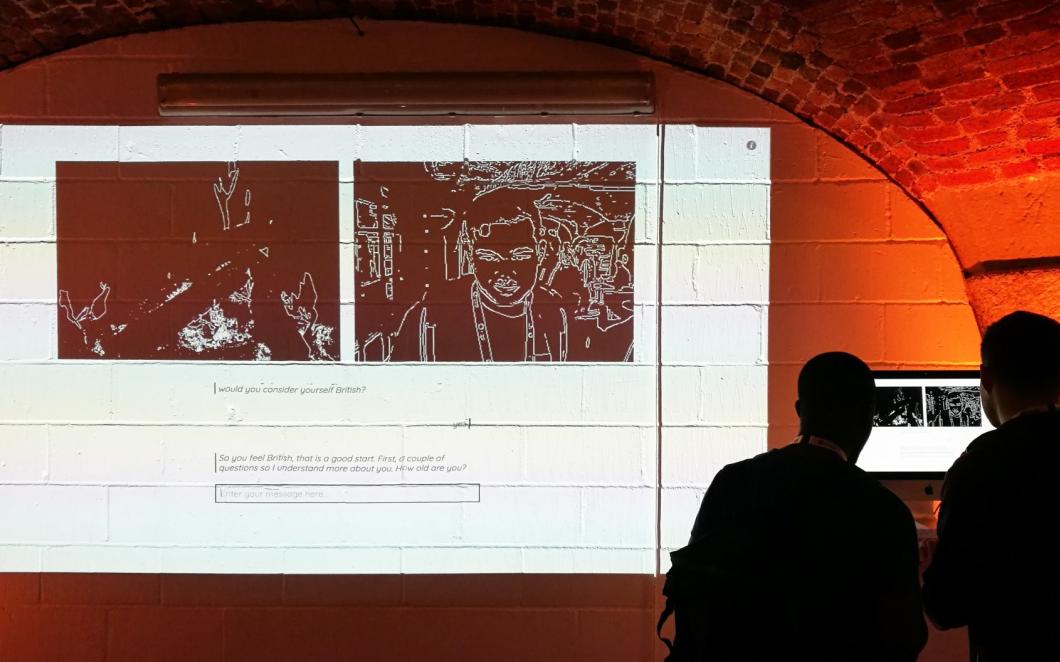

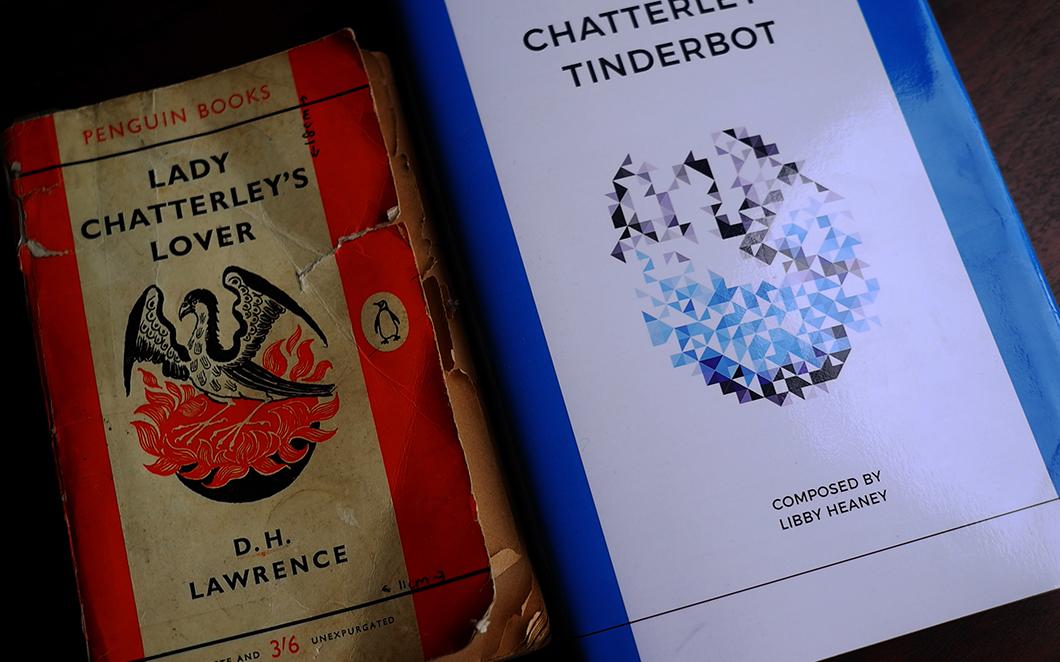

With a chatbot trained on the Life in the UK citizenship test recently released, Somerset House Studios resident Libby Heaney wants to answer the question: how can we create an ethical framework for AI and quantum computing before it’s too late?

The advent of email, instant messaging, and the Internet was as momentous as the invention of telegraphy and the telephone before it. It simultaneously magicked others’ bodies into superfluity, and brought their opinions, thoughts, and routines closer than ever. The growth in the 1990s of forums, personal websites or blogs, and peer-to-peer networking services meant everyday exchanges between regular people happened every day: weekend plans, frustrations, and photographs of meals were all broadcast like a pixelated cablegram. Utopian visions from every political position coalesced around the Internet. It would ring in a new economy, a new era of information exchange. Famously, according to John Perry Barlow’s A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, it would banish the concepts of ownership, status, identity, borders, and consumption. It was an anonymous and immaterial space, boundless and brimming over with possibility.

20-odd years on, the Internet has departed from such lofty expectations: Internet monoliths like Amazon, Google, and Facebook have cast special interest forums, activists’ networks, and the weird wide web into the shadows. Moreover, post-Cambridge Analytica revelations have proved that the Internet and its associated technologies aren’t apolitical realms encased hermetically in the sleek architecture of your phone, computer, or tablet but rather things that are dramatically affected by the a contemporary politics of state surveillance, corporate data mining, and diminishing personal privacy.

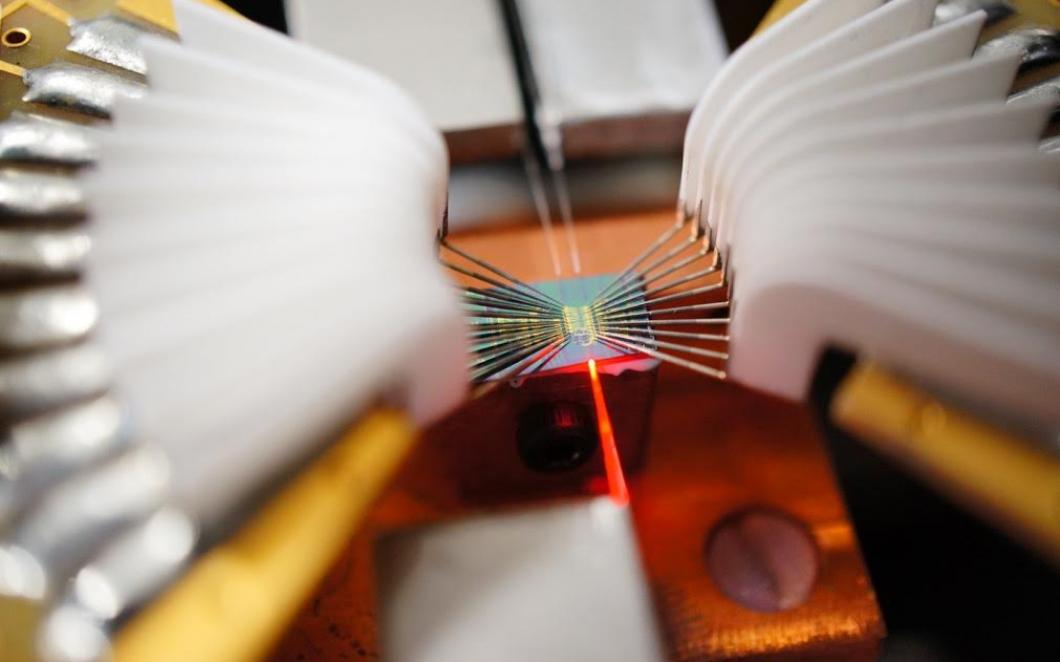

Now, with many companies — Google, Facebook, and Amazon amongst their number — incorporating AI divisions into their businesses, and the prospect of quantum computing in sight, artist Libby Heaney wants her art to interrupt the pace of things.