(For the sake of full transparency I should note here that: ‘The trial was funded by Ravensburger Spieleverlag GmbH (RSV). The funder has no role or ultimate authority in study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the report for publication. RSV has no role in the study, apart from providing the jigsaw puzzles.’)

Maybe my grandmother would have been an ideal puzzle partner. I could have set up a folding table in her bedroom, which always smelled of lavender and Oil of Olay, and it was always quiet there. It just didn’t occur to me that we might have been able to help each other.

*

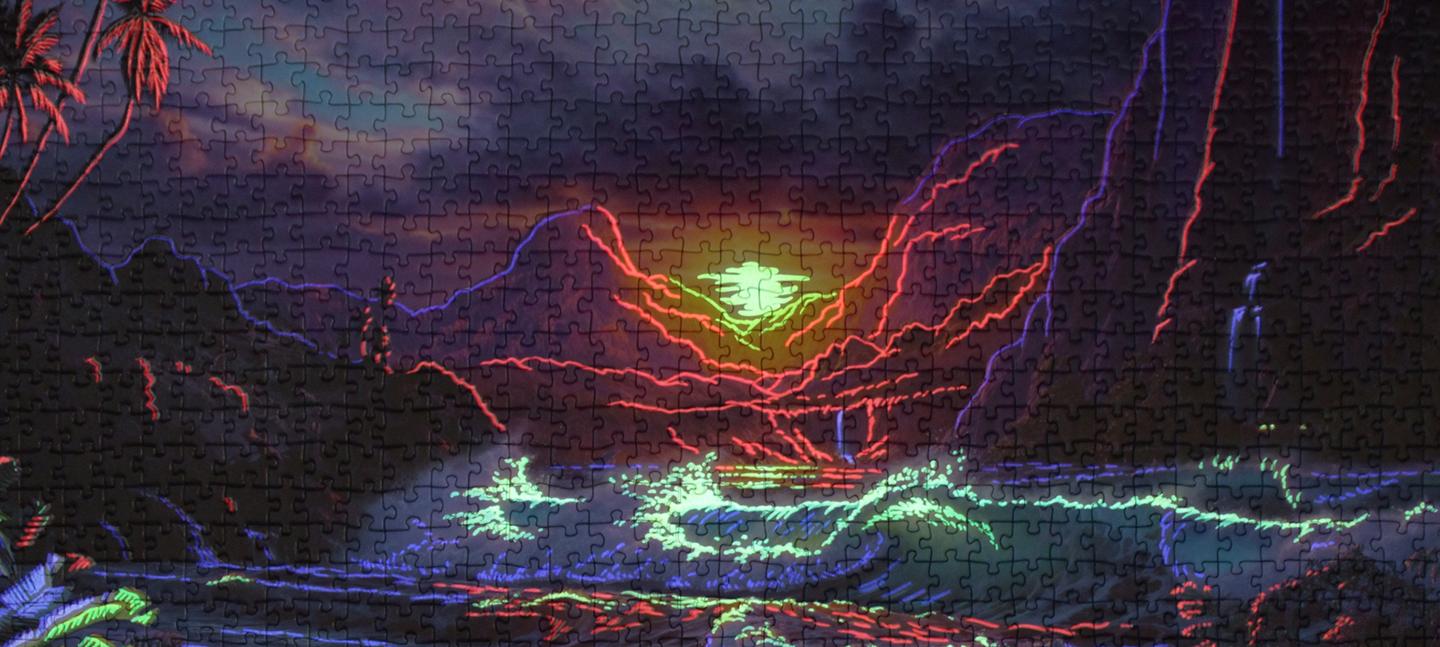

The bittiness of jigsaw puzzles prompted a friend to compare them to cut-ups, a technique which is basically the jigsaw puzzle’s foil. One is about taking something that was unified and exploding it into infinite possibilities, introducing a generative randomness into something given. The other is about taking manifold possibilities and applying process and attention to funnel the fragments into a single picture. I love both, but only the latter will do when the moment comes to pull myself together. (Reader, you must indulge me this one single Dad Joke; there could easily have been many more.)

*

Some of Georges Perec’s observations on jigsaw puzzles in Life: A User’s Manual (1978) strike me as dated, if indeed they were ever apt (real puzzle lovers eschew cardboard puzzles in favour of wooden ones? Seriously?), but most of what he asserts rings true in my experience. We are of a mind on the question of the picture on a puzzle. He writes:

Contrary to a widely and firmly held belief, it does not really matter whether the initial image is easy (or something taken to be easy – a genre scene in the style of Vermeer, for example, or a colour photograph of an Austrian castle) or difficult (a Jackson Pollock, a Pissarro, or the poor paradox of a blank puzzle). It’s not the subject of the picture, or the painter’s technique, which makes a puzzle more or less difficult, but the greater or lesser subtlety of the way it has been cut…

However, my distinction in terms of the image is less about difficulty (I have only ever accessed the machine-cut cardboard puzzles which Perec subordinates to hand-cut wooden ones). It’s about attachment to process. I have a strong preference for puzzles that don’t culminate in an image that I find especially pleasing. I don’t want to be responsible for the completion or not of the Sistine Chapel; give me the stupid basket of kittens any day.

When I was working on my PhD (a protracted and maddening encounter with racism, misogyny, class bias, ableism and the inevitable gaslighting that cements these oppressions into the neoliberal university experience) I moved continuously between my laptop and a jigsaw puzzle. When my frustration with the writing reached a zenith and my mind felt full of static, I’d turn to my puzzle and let my writing brain run in the background. And when I’d had enough of dealing with some intricate dangle of foliage or impossible block of blue, for example, and nothing seemed to fit together, the composition of tricky sentences and the building of arguments seemed like a piece of cake. Back and forth, each problem took its turn as the problem, and both required a similar commitment to just getting it done. Completion, not brilliance, not even beauty, was the goal of each.

*

‘The pieces are readable, take on a sense, only when assembled; in isolation, a puzzle piece means nothing – just an impossible question, an opaque challenge. But as soon as you have succeeded, after minutes of trial and error, or after a prodigious half-second flash of inspiration, in fitting it into one of its neighbours, the piece disappears, ceases to exist as a piece. The intense difficulty preceding this link-up – which the English word puzzle indicates so well – not only loses its raison d’être, it seems never to have had any reason, so obvious does the solution appear.’ Perec, 1978

*