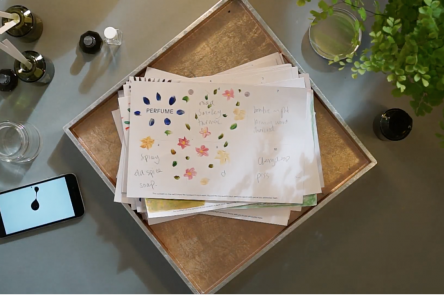

Perhaps, in a fast-changing world, it is natural to look for little oases of permanence, where traditional practices still reign. Perfumery is often presented this way: jasmine petals collected on dewy mornings in Provence; inspired ‘noses’ blending rare essences in darkened rooms. But the truth is that perfumery has for some time been undergoing a revolution of which few people outside the industry are aware. Much as electronics opened up the world of music to new sounds and new ways of composing, so synthetics – lab-created aromatic molecules – have opened up the world of perfume. In both cases there’s been scepticism, as though synthetics must automatically be inferior. Promotional descriptions of perfumes often omit any mention of their non-organic ingredients, even when those are in the majority. So your perfume will claim to be made of ylang-ylang, orris, and oakmoss, but they don’t mention the hexyl Cinnamaldehyde or the Gamma Octalactone or the Ambroxan. Similarly, when music critics write about recordings they hardly ever mention the technology of recording and the banks of highly specialised electronic tools like adaptive limiters and a-to-d convertors and granular synthesizers. All that stuff – made in labs and workshops – is as mysterious and unmentioned as, say, cis-3-Hexen- 1-ol (fresh cut grass) or Skatole (faeces, or in dilution, white flowers).