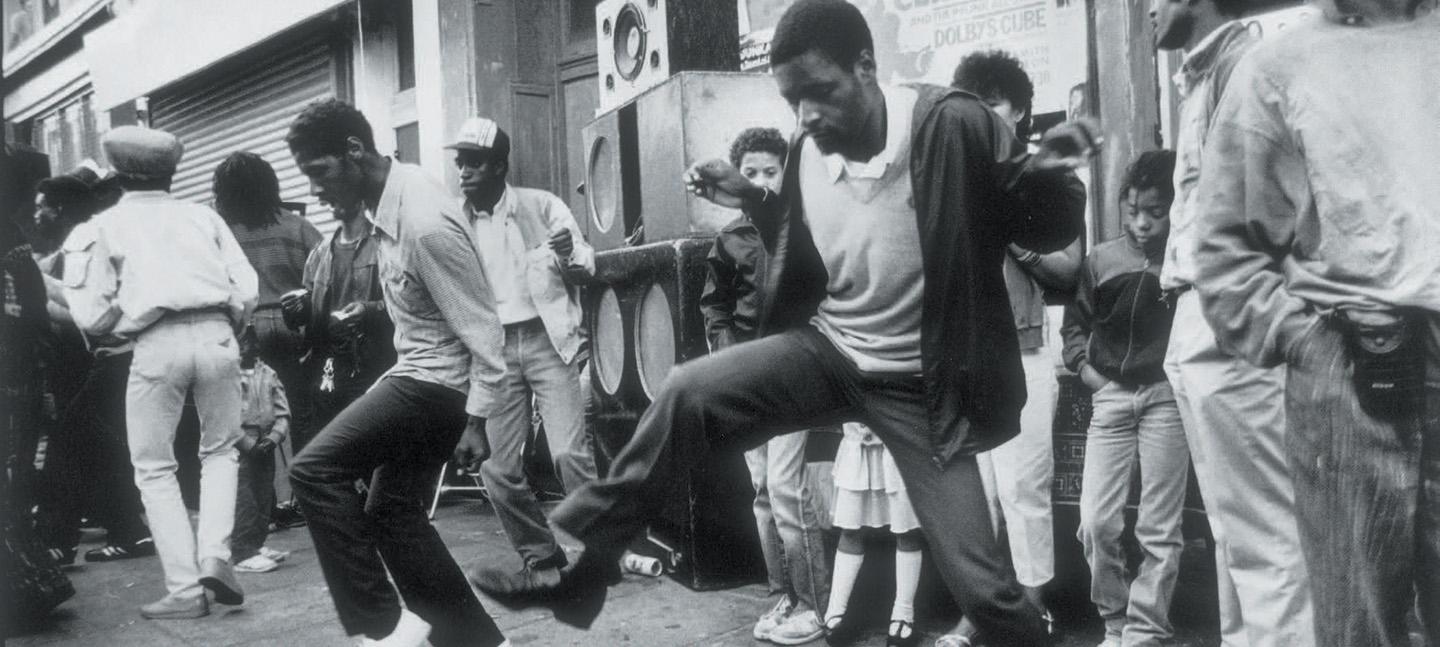

Writer, educator, broadcaster and musician Vivien Goldman explores the impact of the Windrush generation on British music culture in the second half of the 20th century.

They came with dreams and, in some cases, collections of vinyl 45s that would spin on to change the sound of pop and the face of Britain’s communities. Garage, grime, warehouse parties, rave, the supremacy of acts like Stormzy, come to that the whole field of music would not exist in its popular form without the extraordinary contribution to British culture made by immigrants from the West Indies and their descendants.

It has grown from the first big Jamaican hit, Millie Small’s My Boy Lollipop in 1964 and evolved through reggae’s Steel Pulse in the 1970s to the chart-topping grime of Dizzee Rascal, Wiley and Dave today. Creators of Caribbean descent have consistently produced a reverse cultural colonialism, changing forever the country whose riches were made possible by unpaid captive labour.