What are the common themes in your work?

I always want to tell stories relating to the diasporic condition - of belonging, or not belonging. I want (my work) to show our complexities in ways that can't be misconstrued or co-opted. I'm constantly trying to create languages that are robust and multilayered enough to house those of us who are often sidelined or marginalised by the dominant voice.

Tell me about your background.

I was born in Kenya, I grew up in the Middle East and I came to England when I was 16. Then I moved to London to go to Art school, I did a foundation course at Saint Martins, then I did painting at The Slade (UCL) and then I went back to Saint Martins to do animation.

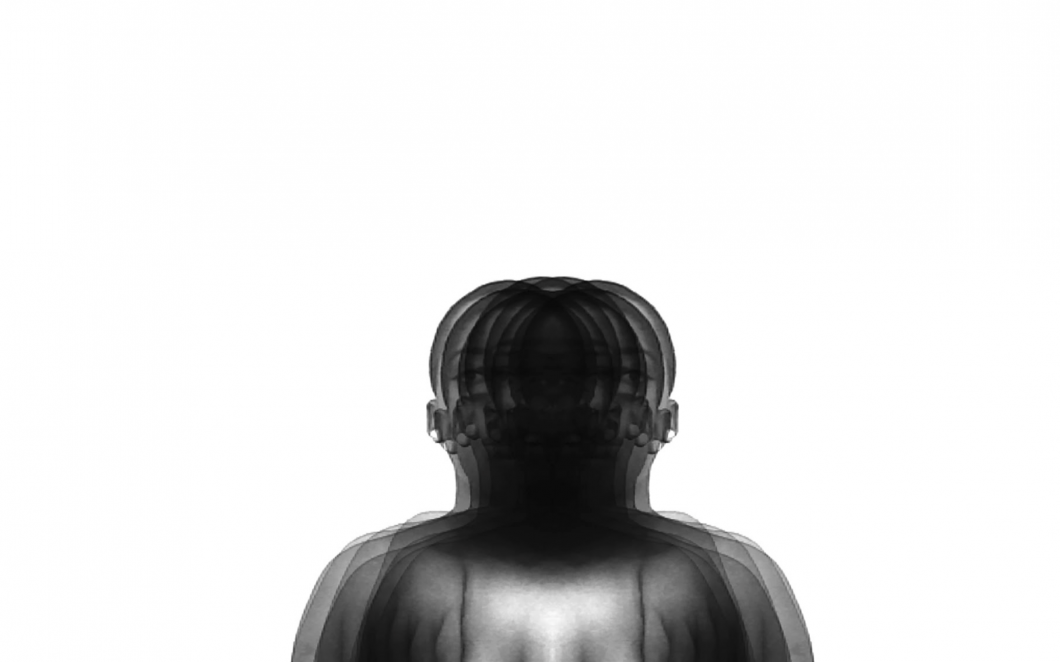

It’s interesting that this piece focuses on movement, given you’ve been quite nomadic in life. What have you noticed as an artist commenting on identity while traversing different cultures?

It's a different proposition everywhere you go, you are read differently according to the context you are in. My identity – and in extension my work – is perhaps read differently here, to how it would be read in Nairobi, or in New York. I don't feel tied to place really, more to people, and I'm more about exploring the ocean of the in-between, the space between here and there. As James Baldwin said, “The place in which I'll fit will not exist until I make it.”

Do you prefer being elsewhere rather than the London scene?

London is a bit like a toxic lover. It treats you badly, but you keep coming back. My gallery is in New York. I do see a difference between the UK and America. I think that there's more black philanthropy in the US which makes it a very different marketplace and different conversations. I've just been in Rome for a fellowship and gave up my studio here because I thought I'd move to New York permanently but I missed London a lot (laughs). I'm not black British, I don't feel my history is here but I also very much don't feel like I can take on the African American-centric point of view in my work. There's still so much we need to do, but I appreciate the conversation here around blackness and what it means here in this space. If you just move to America, all those nuances can be swallowed a little bit.

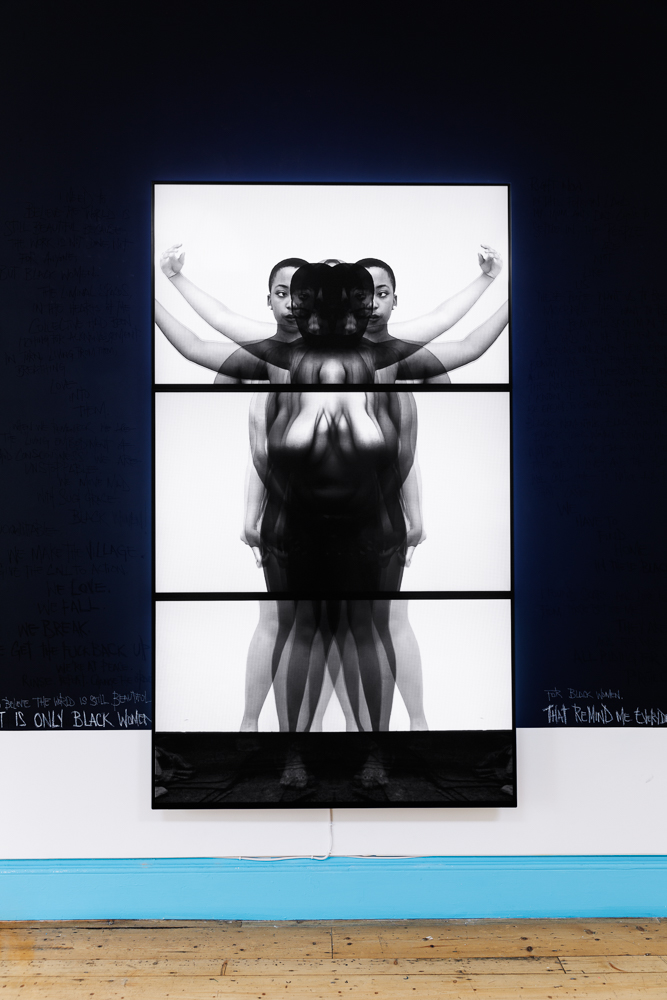

Get Up, Stand Up Now, is a survey of British black art. Is it important that we keep creating spaces to present black creativity?

I really admire and respect Zak and his dad Horace so I was delighted to be a part of this. It was brave and bold of him to take from the archives - which felt like a very loving gesture - and to then branch that out to people who speak both directly and indirectly to Horace's legacy and hopefully push it forward. I went to the opening...you could tell it was full of love. And love is strength, right? It's a powerful force.

I had been curious to see how it would work, who he would include and what that inclusion would mean. I feel like sometimes these things can serve as a distraction rather than progression for working black artists in a realm which is predominantly white.