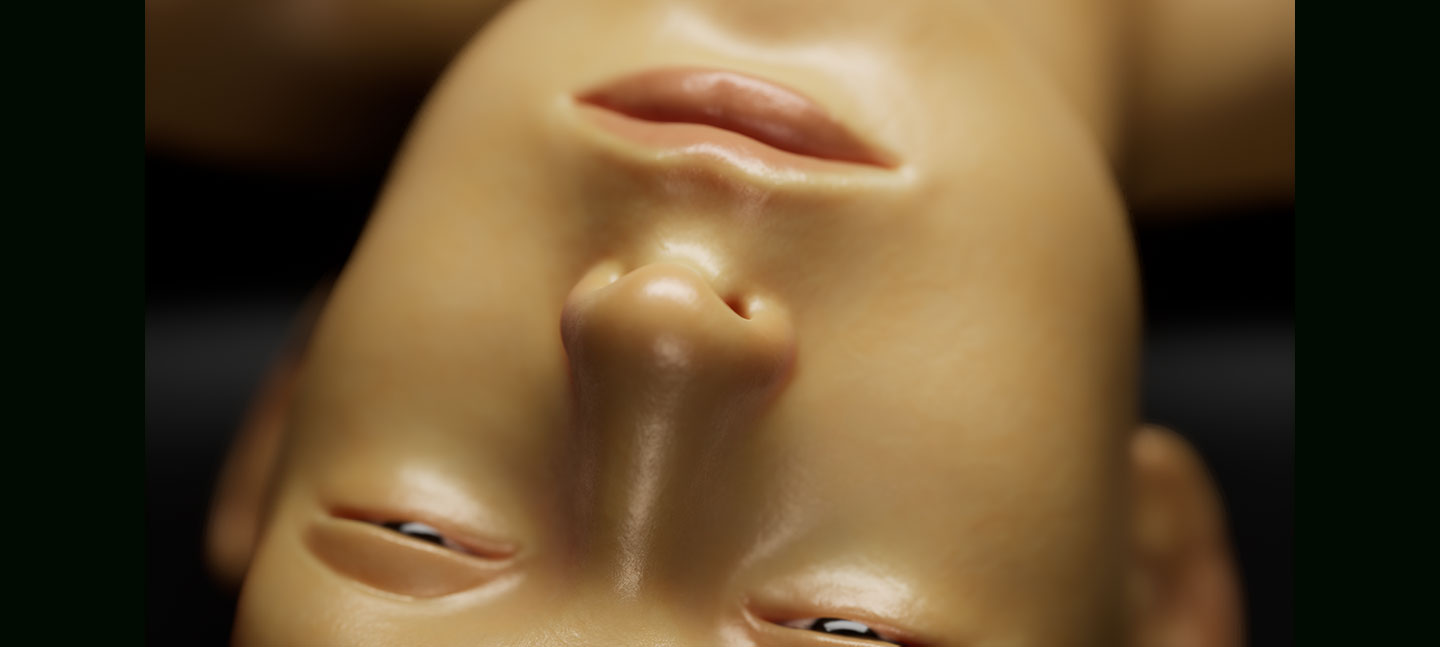

Paul Maheke's work 'The River Asked for a Kiss' which features in Get Up, Stand Up Now, is a memorial to Gambian refugee Pateh Sebally who drowned in Venice’s Grand Central. Kemi Alemoru interviews Maheke on his complex creative process, and the racial politics of the art world.

"He is stupid. He wants to die," one person says in the grainy video that surfaced online in 2017. At just 22, Pateh Sebally, a Gambian refugee, struggled in Venice’s Grand Central canal, failing to tread water while onlookers and tourists filmed and jeered telling him to “go home”. There were many present for his death, but what eventually overpowered him was the romanticised water of the floating city. The same waters drew the tourists who failed to act with compassion, and water is what carries large number of migrants from Gambia and beyond to Italy and its neighbouring European countries. It is all at once a life source, a lifeline, and a threat.

While Paul Maheke’s work tells the stories of Pateh, the diaspora, and nature as a whole, it does so through water, an entity he believes connects everything. “It's something that a lot of us can relate to, we all have a relationship with water even if it has played a different role in your culture,” he explains. “We need it to live, we're surrounded by it. Yet there's still such a mystery to it. That's quite beautiful.”

Hailing from France, and hopping from Canada to the UK, Maheke has learnt that there are innumerable ways to look at a subject and that informs his multi-layered and deliberately abstract art. He adds: “I like responding to a given situation that may appear obvious, and then I try to complicate the narrative around it.”

Screenshot 2019-08-29 at 12.45.48.png