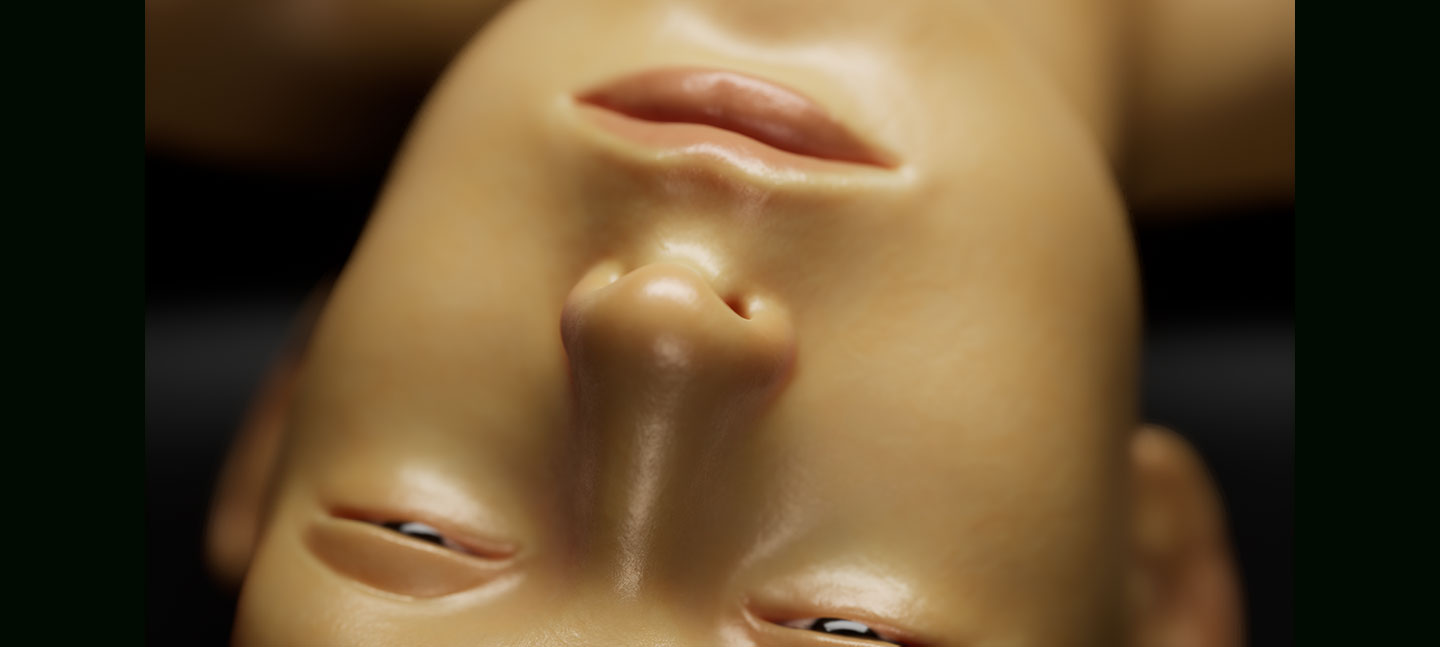

Deborah Roberts makes collages using photographs, magazine clippings and images from the Internet. She creates a unique visual language, evoking African-American womanhood, to explore the subjects of beauty, identity and politics. Forcefully confronting the hyper-sexualisation of women, and the media’s privileging of whiteness and youth, Roberts' figures often take the form of young African girls whom she presents with strength and power. Her composite figures represent an expanded view of beauty that prioritises marginalised narratives, while fighting discriminatory perceptions of the Black female experience. Her Untitled piece in Get Up, Stand Up Now suggests bodily fragmentation, but the composite figures at the forefront of her world also exude imagination and vitality.

I absolutely loved your piece in the exhibition. Did you start out wanting to do a portrait of a little girl, or was the process more organic?

Well, all my works are of girls. I was working within notions of blackness and black beauty and identity politics, the way they have historically been structured. Where if you do not have blonde hair and blue eyes, then you aren’t considered beautiful. All my work was coming from that idea.

Is your piece part of a series?

No, it’s one individual piece. The way I work, I ask ‘what do I want to talk about?’ Do I want to talk about police violence? Do I want to talk about people not putting black kids on pedestals? It depends. At that time [it was] the freedom to walk down the street uninhibited, the idea of being free. I always tell people there are only two Black kids I know who are free in America, and that's Willow Smith and her brother. They are free people, they seem like they don't have that baggage that we carry, even though it has to be on them. So this piece in particular, it was along those lines.

Do the different parts of the collage mean anything in particular?

When I talk about the west, it's a white hand coming out of her back. She has a more African pattern on her skirt, her lower body; the subtext to that is that she birthed black babies and black individuals. And I took her hands and folded them.

Yeah, one hand is sort of pulled in, curved towards her.

That to me is a coping mechanism. When people get in my face, the first thing I do is cross my hands, so I'm saying you have crossed the line.