NA We’ve talked about the inherent violence in these dynamics of where the lens or the camera is pointing and who is looking back. However, there's something materially significant about the camera too, in relation to colonial histories, ecologies, and specifically, the colonial violence that has been inflicted on non-humans, other-than-humans, or more-than-humans (there are many ways to talk about these worlds). I’m thinking about all technological industries, embedded in a fast paced capitalist extraction economy, which sustain present-day colonialism by unearthing raw materials to manufacture our devices. The camera is embedded in these dynamics, too. I was wondering about your relationship to the materiality of the camera as an object that has built into it the very politics that you use the camera to explore.

AV I don't think any instrument is innocent. Consider the way many cave paintings were made with animal blood. As a technology of the 20th century, the moving image camera contains and embodies the resources, struggles and paradoxes of Western modernity.

Yet the question of representation is ancient.

Now, of course, everyone knows that the development of lenses and cameras is completely intertwined with the military and mining industries as is this computer that we are now using to speak with each other.

NA Exactly, all technology.

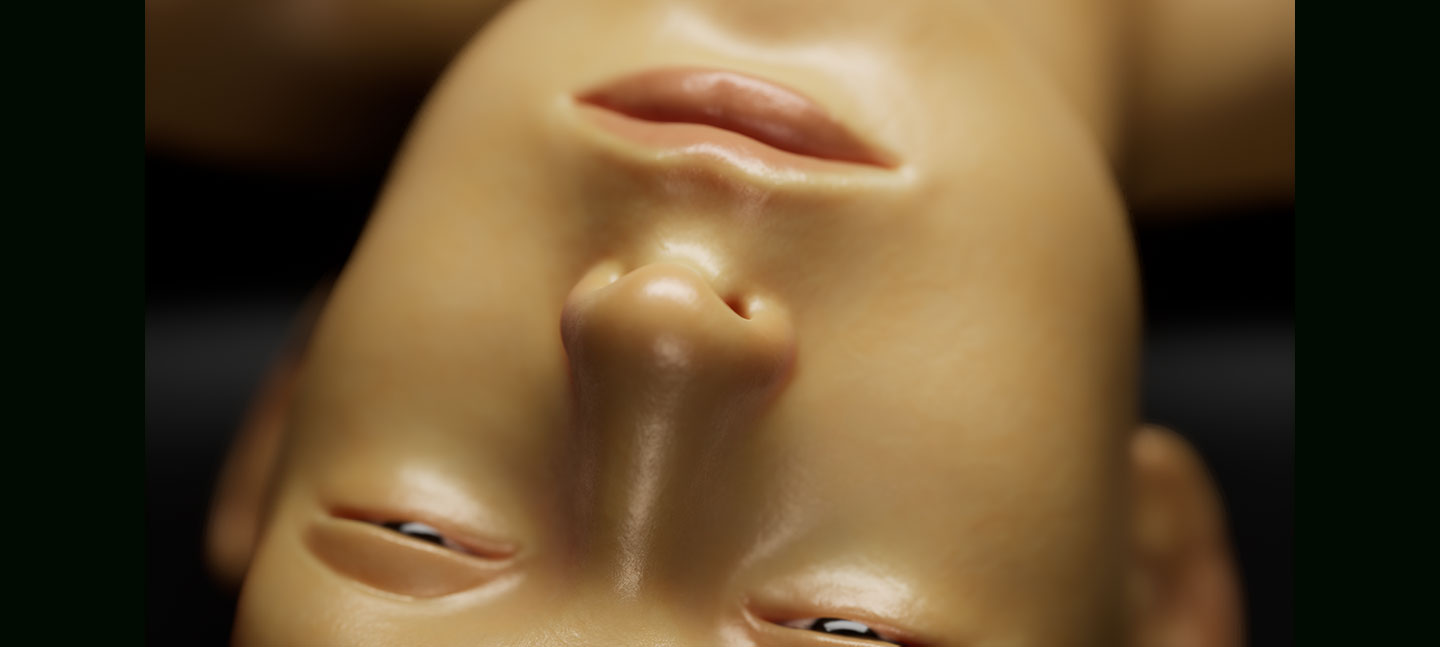

AV Now addressing your question about the materiality of the camera and my relationship to it, I have chosen to work with analog 16mm cameras over the past many years as I feel these cameras were made to last and they do. I am not really that interested in the novel developments of digital image technology that seem to grow old in an instant, producing an enormous amount of waste. The film industry is obsessed with novelty and consistently erasing the past. I am rather interested in working with a dying medium, threatened of extinction.

The alchemical and unexpected process of making analogue images is for me a way to experiment and ritualise the way in which I make films. However, I am not saying that making analogue images is saintly, it also depends on toxic chemicals and minerals that pollute and intoxicate. I would actually say that there is an inherent toxicity to image making.

I was recently writing an essay about British filmmaker Sandra Lahire, whose films deal precisely with the toxicity of mining against a certain toxicity of image making. Looking back at her films, I came to think of the role and ominous presence of X-ray images and the way in which in the end, cinema is in itself a kind of X-ray machine. So I would rather take cinema as an X-ray machine, a toxic technology that aids in diagnosing pathologies. I'm interested in that: how can cinema be an X-ray machine of sorts? What kind of radiography can it produce? Can it enable us to see, to sense, to understand something intangible?